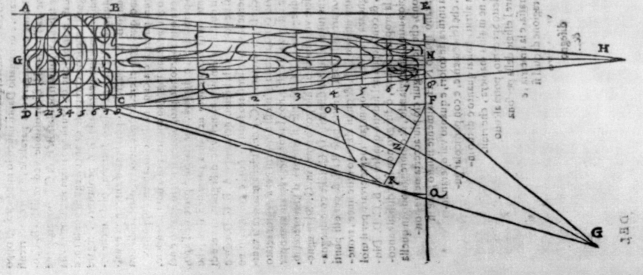

Pietro Accolti, Prospettiva Pratica (Florence, 1625), anamorphic projection

Architecture is the praxis that takes our collectively held ideologies, attitudes, and understandings, and puts them concretely into the world. In so far as architects are asked to transform our environment by putting new bits in and removing old bits, architects do something other professions do not do. When a client commissions an architect to build, e.g., a hospital, the architect is asked to take our collectively held views on hospitals and health care generally – all our collectively held ideas, knowledge, attitudes, prejudices even – and put them into material form. In order to do this, the architect must reflect upon these social formations. S/he must internalize them and project them into the environment. This is the architectural meaning of the word project, and the definition of the architecture project [Tafuri].

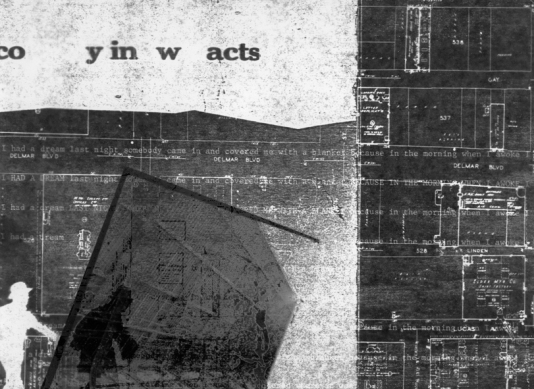

These social formations are collectively held, but they are transformed into the particular, material and spatial form of a building by a process that is channeled through the reflection of a single architect. Society places a burden of trust on architects. How accurate a reflection, how comprehensive a materialisation, depends upon the capacity of the architect to reflect, and the capacity of the design process to allow for reflection. Architects reflect by drawing. This is what happens when a client briefs an architect, the architect briefs his/her design team, the design team returns to the client with a design proposal.

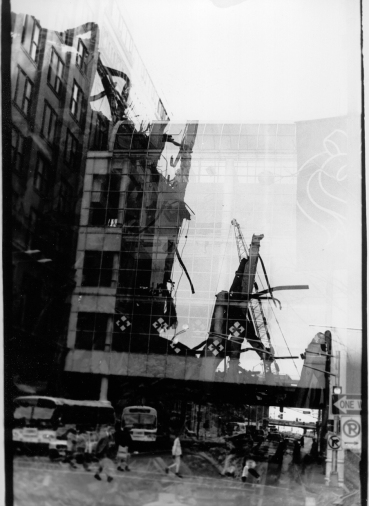

Every time someone throws a Sainsbury cart through a storefront (an act that is not without a certain social integrity or legitimacy), or a volume home builder puts 500 homes on a site in the beltway, a social formation is concretised in the world. The difference between the architecture project on the one hand and a riot or sub-development on the other, all of which are radical projections of a social formation into a physical one, is that the latter are forms of acting out. The riot in particular is a form of class action that has not been sublimated through a process of reflection. Both issue from an unmediated drive that is creative-destructive [Schumpeter’s gale, Klee’s angelus novus]. These transformations of the environment occur without reflection on our collectively held views, or at least without reflection in a form that is recorded in a design process. They are not architecture projects in the architectural sense of project: a trope that goes from the conceptual and collective to the material and particular. It is reflection which gives the architecture project its fictive quality, a quality that the riot or sub-development will never have.

We are reasserting here a version of Mies’ thesis that architecture is the expression of the zeitgeist, the spirit of the age. Except instead of spirit [Hegel], we are speaking about a form of class consciousness [Hegel, via Marx].

The architecture project is a form of materialisation of class consciousness [Marx], except that it is more often than not class unconsciousness, because many of the ideas, presuppositions, prejudices, clichés, ideologies that we hold collectively, we are unaware of. It takes a form of cultural analysis, which proceeds as a form of reflection upon our artefacts, to make them manifest, explicit, conscious. The collective unconscious is the library from which Rossi’s collective memory draws forth its forms. The project makes conscious, i.e., puts into material space and form, the social formations that had hitherto remained hidden. To go from concept to material, hidden to visible, latent to manifest, unconscious to conscious, inside to out, are different glosses on the idea of the project, which involves a transformation.

Reflection involves introjection [Lacan] as well as projection. The architect has to internalise the social formation that s/he finds her/himself amidst – inhale this ambient social cloud, as it were – before it can be projected as material form.

Note: Throwing a cart through a storefront is a form of projection, but no reflection on social life has been undertaken and consequently, there has been no transformation from conceptual to material. It simply involves the translation of material from one location to the other, like vomit.